Regulating Online Pharmacies & Medicinal Product E-Commerce

The internet has led to an increase in e-commerce of prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) medicinal products; one in four adults has purchased medicines online.1 ,2 This expansion of e-commerce in pharmaceuticals has greatly improved many companies’ bottom lines. For example, in 2017, the Chinese company Ali Health reported a 739% rise in its revenue driven by e-commerce of over-the-counter medicinal products alone.3 For consumers, online pharmacies offer many advantages, including lower costs, convenience, privacy, and a wider range of choices.4 For businesses, using online platforms and removing the need for physical storefronts translates into the multiplication of stock-keeping units and increased price competitiveness.

- 1Orizio, G., A. Merla, P. J. Schulz, and U. Gelatti. “Quality of Online Pharmacies and Websites Selling Prescription Drugs: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 13, no. 3 (September 2011): e74. doi:10.2196/jmir.1795

- 2Statista. “Online Drug Sales: Sales—Usage—Attitudes. Consumer Survey 2017, e-Commerce and Retail.” Accessed 11 June 2019. https://www.statista.com/study/46027/online-drug-sales-sales-usage-attitudes

- 3Perez, B. “Alibaba Health Revenue Soars on Robust Online Pharmacy Sales.” South China Morning Post. Published 17 May 2017. http://www.scmp.com/tech/china-tech/article/2094681/alibaba-health-revenue-soars-robust-online-pharmacy-sales

- 4Orizio, G., and U. Gelatti. “Human Behaviors in Online Pharmacies.” In Encyclopedia of Cyber Behavior, 661–670. Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2012. doi:10.4018/978-1-4666-0315-8.ch056

Although e-commerce of medicinal products has many benefits for patients and the pharmaceutical industry, it remains a concern for regulatory authorities (RAs) worldwide. Regulatory Authorities must safeguard the public from potential harm posed by illegitimate online pharmacies. Existing laws may need to be amended, and enforcement approaches changed, to address the transnational nature of e-commerce of medicines.

Note: In this article, “e-commerce” refers to the commercial transaction of buying and selling goods and services over the internet.5 “Medicinal products” refers to prescription and over-the-counter medicines, and excludes nutritional supplements. “Controlled substances” refers to substances likely to cause dependence when abused, such as amphetamines, morphine, and codeine.6 “Counterfeit medicines” refers to medicinal products that are substandard or falsified, with fraudulent misrepresentation of their identity, content, or source.7

Safety Concerns

According to a 2016 report published by the Center for Safe Internet Pharmacies, 96% of online pharmacies worldwide do not comply with the relevant laws of countries within which they operate.8 In addition, some online pharmacies have sold counterfeit medicines, defrauded consumers, and stolen customer credentials and credit card information.9 ,10

Despite rigorous educational efforts, many consumers remain unaware of the safety risks posed by counterfeit medicines.10 ,11 Prescription-only medicines (POMs) can be easily purchased from online pharmacies and popular consumer-to-consumer e-commerce platforms, such as Lazada and Carou-sell, due to the lack of regulations from regulatory authorities.12 ,13 The availability of prescription-only medicines from online pharmacies, whether legitimate or not, is a serious public health concern, especially as more consumers use the internet to self-diagnose and self-treat.14 The unsupervised use and potential misuse of prescription-only medicines can lead to severe adverse effects and even death.15

Current Efforts to Protect Consumer Safety

At present, regulatory authorities rely on a collection of legal regulations, international law enforcement operations, and accreditation programs to address safety concerns related to the e-commerce of medicinal products.

US Legal Restrictions on Online Sales

Laws regulating the online sales of medicinal products vary from country to country. In the US, the Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 2008 strictly restricts consumers’ online access to controlled substances.16 Online pharmacies dealing with controlled substances must register with the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). Consumers must also complete an in-person medical examination by a qualified practitioner to obtain a valid prescription before they can purchase controlled substances. Hefty penalties serve as a deterrent to individuals who intend to engage in unauthorized sales of controlled substances.17 Laws regulating online sales of medicinal products in other countries are reviewed later in this article, in the Regulatory and Enforcement Challenges section.

Laws Against Counterfeit Medicines

The Drug Supply Chain Security Act and the Falsified Medicines Directive (FMD) are legislative tools used by the US and the European Union, respectively, to address the dangers of counterfeit medicines. By creating an interoperable electronic track-and-trace system, regulatory authorities aim to prevent counterfeit medicines from entering the legitimate supply chain.18 ,19 To ensure that the supply chain is secure, key supply chain stakeholders such as manufacturers, repackagers, distributors, and pharmacies must ensure the authenticity of products at the point of receipt before handing them over to the next party in line.18 ,19

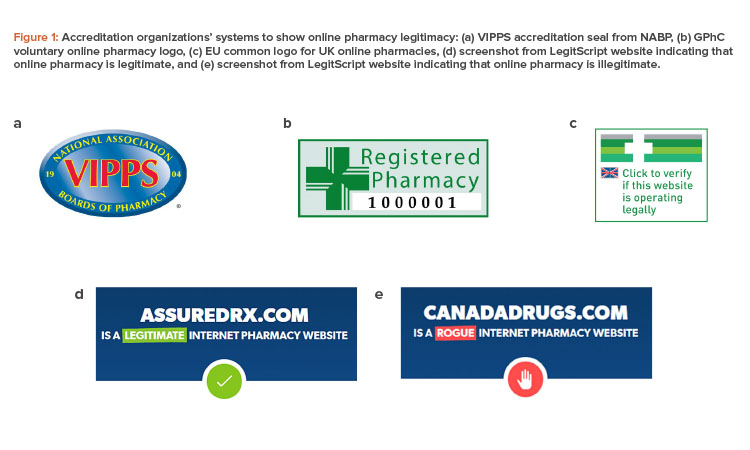

Under Falsified Medicines Directive, EU-based online pharmacies must obtain a common logo from the national regulatory authorities to display on their website.20 Clicking the logo directs the consumer to the pharmacy’s entry on the regulatory authoritie’s online list of authorized/registered pharmacies, thus verifying that the pharmacy site is legitimate.

International Law

The MEDICRIME Convention, an initiative of the Council of Europe, is the first international treaty to criminalize online sales of counterfeit medicinal products.21 Individuals engaged in such sales will be prosecuted regardless of the country where the act was committed. For greater effectiveness, more regulatory authorities worldwide should ratify the MEDICRIME Convention and enact domestic laws to criminalize online sales of counterfeit medicinal products.

Launched in 2008, Operation Pangea is the leading international collaborative enforcement effort to eradicate illegal online sales of medicinal products. For example, in 2017, law enforcement agencies such as customs, police forces, and regulatory authorities successfully seized US$25 million worth of illicit and counterfeit medicines,22 illustrating the effectiveness of collaborative efforts among different agencies when dealing with transnational crimes.

Nonetheless, illegal online sales of medicines are still prevalent.22 Regulatory Authorities may need to reevaluate Operation Pangea, expand its scope, and develop new approaches to address illegitimate online pharmacies, involving major pharmaceutical companies in their efforts where necessary.

Accreditation Systems

Accreditation systems can help improve information asymmetry and offer safety assurance to consumers.23 For example, these systems provide tools such as accreditation seals or website checkers that verify the legitimacy of online pharmacies. However, many consumers are unaware of the existence and purpose of accreditation systems,24 and some illegitimate online pharmacies have used fake accreditation seals on their websites to deceive unsuspecting consumers.25 Table 1 reviews selected accreditation organizations for online pharmacies,20 ,26 –31 and Figure 1 displays selected accreditation seals.

The lack of standardized criteria and other lapses in compliance checks have led to inadvertent accreditation of illegitimate online pharmacies, thereby threatening patient safety.26 Hence, regulatory authorities need to apply standardized criteria for accreditation systems. They also must educate consumers on safer practices for purchasing medicines online, such as how to differentiate between authentic and inauthentic accreditation seals.

| Accreditation Organization | Countries of Operation | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| National Association of Boards of Pharmacy (NABP) |

US and Canada |

|

| General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC) |

Great Britain |

|

| RAs of EU member states | EU member states |

|

| LegitScript | International |

|

| PharmacyChecker | International |

|

- 5Cambridge Dictionary. “e-commerce.” Accessed 11 June 2019. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/e-commerce

- 6US Department of Justice and Drug Enforcement Administration, Diversion Control Division. “Controlled Substance Schedules.” Accessed 11 June 2019. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/schedules

- 7World Health Organization. “Definitions of Substandard and Falsified (SF) Medical Products.” Accessed 11 June 2019. http://www.who.int/medicines/regulation/ssffc/definitions/en

- 8LegitScript and the Center for Safe Internet Pharmacies. “The Internet Pharmacy Market in 2016: Trends, Challenges and Opportunities.” Published January 2016. http://safemedsonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/The-Internet-Pharmacy-Market-in-2016.pdf

- 9United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute. “Counterfeit Medicines Sold Through the Internet.” Published 2011. https://docplayer.net/20033826-Counterfeit-medicines-sold-through-the-internet.html

- 10 a b Alliance for Safe Online Pharmacies. “New Survey Reveals Majority of Consumers Are Unaware of Risks Associated with Online Pharmacies, Oppose Legalizing Prescription Drug Importation” (press release). MarketWatch. Published 19 July 2017. https://www.marketwatch.com/press-release/new-survey-reveals-majority-of-consumers-are-unaware-of-risks-associated-with-online-pharmacies-oppose-legalizing-prescription-drug-importation-2017-07-19

- 11United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute. “Consumers’ Awareness on Internet Sales of Counterfeit Medicines.” Published 2013. http://www.unicri.it/topics/counterfeiting/medicines/savemed/FINAL_Report_Guidelines_awareness_050213_withD8.3.pdf

- 12Liang, B. A., T. K. Mackey, and K. M. Lovett. “Illegal ‘No Prescription’ Internet Access to Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs.” Clinical Therapeutics 35, no. 5 (2013): 694–700. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.03.019

- 13Ivanitskaya, N., J. Brookins-Fisher, I. O’Boyle, D. Vibbert, D. Erofeev, and L. Fulton. “Dirt Cheap and Without Prescription: How Susceptible Are Young US Consumers to Purchasing Drugs from Rogue Internet Pharmacies?” Journal of Medical Internet Research 12, no.2 (2010): e11. doi:10.2196/jmir.1520

- 14Robertson, N., M. Polonsky, and L. McQuilken. “Are My Symptoms Serious Dr Google? A Resource-Based Typology of Value Co-Destruction in Online Self-Diagnosis.” Australasian Marketing Journal 22, no. 3 (2014): 246–56. doi:10.1016/j.ausmj.2014.08.009

- 15Cicero, T. J., and M. S. Ellis. “Health Outcomes in Patients Using No-Prescription Online Pharmacies to Purchase Prescription Drugs.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 14, no. 6 (2012): e174. doi:10.2196/jmir.2236

- 16US Department of Justice. Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 2008. https:www.justice.gov/archive/olp/pdf/hr-6353-enrolled-bill.pdf

- 17Schultz, B. “Online Pharmacy Regulation: How the Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act Can Help Solve an International Problem.” San Diego International Law Journal 16, no. 2 (2015): 381–416. https://digital.sandiego.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1033&context=ilj

- 18 a b US Food and Drug Administration. “Guidance for Industry: DSCSA Implementation: Product Tracing Requirements—Compliance Policy.” Published December 2014. https://www.fda.gov/media/90397/download

- 19 a b European Commission. “Falsified Medicines.” Accessed 20 August 2019. https://ec.europa.eu/health/human-use/falsified_medicines_en

- 20 a b c European Commission. “EU Logo for Online Sale of Medicines.” Accessed 20 August 2019. https://ec.europa.eu/health/human-use/eu-logo_en

- 21Council of Europe. “The MEDICRIME Convention.” https://www.coe.int/en/web/medicrime/the-medicrime-convention

- 22 a b Interpol. “Millions of Medicines Seized in Largest INTERPOL Operation Against Illicit Online Pharmacies.” Published 25 September 2017. https://www.interpol.int/News-and-Events/News/2017/Millions-of-medicines-seized-in-largest-INTERPOL-operation-against-illicit-online-pharmacies

- 23Bate, R., G. Jin, and A. Mathur. “In Whom We Trust: The Role of Certification Agencies in Online Drug Markets.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series 17955 (2012): 3–28. https://ideas.repec.org/p/nbr/nberwo/17955.html

- 24Kim, D. J., D. L. Ferrin, and H. R. Rao. “A Trust-Based Consumer Decision-Making Model in Electronic Commerce: The Role of Trust, Perceived Risk, and Their Antecedents.” Decision Support Systems 44, no. 2 (2008): 544–64. doi:10.1016/j.dss.2007.07.001

- 25US Government Accountability Office. “Internet Pharmacies: Federal Agencies and States Face Challenges Combating Rogue Sites, Particularly Those Abroad.” GAO-13-560. Published 8 July 2013. https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-13-560

- 26 a b Horton, J. “Yet Another CIPA- and PharmacyChecker-Certified Internet Pharmacy Criminally Charged for Selling Bad, Non-Canadian Medicines” [blog post]. LegitScript website. Published 28 March 2017. https://www.legitscript.com/blog/2017/03/yet-another-cipa-andpharmacychecker-certifi ed-internet-pharmacy-indicted-for-selling-bad-non-canadian-medicines

- 31 a b PharmacyChecker website. Accessed 11 June 2019. https://www.pharmacychecker.com

- 27 a b National Association of Boards of Pharmacy. “Verified Pharmacy Program.” Accessed 11 June 2019. https://nabp.pharmacy/programs/verified-pharmacy-program

- 28National Association of Pharmacy Regulatory Authorities. “Online Pharmacies.” Accessed 11 June 2019. http://napra.ca/online-pharmacies

- 29General Pharmaceutical Council. “Internet Pharmacy.” Accessed 11 June 2019. https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/registration/internet-pharmacy

- 30LegitScript website. Accessed 20 August 2019. https://www.legitscript.com

The “.pharmacy” Domain

The “.pharmacy” domain scheme complements national accreditation systems to verify the legitimacy of online pharmacies. It was launched by NABP in 2014 to provide consumers worldwide with a way to identify safe, legitimate, and ethical online pharmacies.27 ,28 As the owner of the “.pharmacy” domain, NABP determines which pharmacies to host on the domain and requires that they demonstrate legitimacy. Regulatory Authorities may audit NABP periodically to ensure its reliability and fairness in implementing this scheme.

Regulatory and Enforcement Challenges

To ensure the safety of medicinal product e-commerce, regulatory authorities need relevant legislation as well as adequate resources to find and prosecute criminals. However, in many countries, laws are insufficient to regulate the sales of medicinal products. Moreover, jurisdictional and resource limitations often allow criminals to escape prosecution.

Lack of Strong National Laws Worldwide

Unfortunately, 66% of countries worldwide do not have laws that explicitly regulate or prohibit online sales of medicinal products32 Prescription-only medicines and over-the-counter medicinal products can therefore be sold on e-commerce platforms by anyone. As a result, regulatory authorities in these countries are only able to employ the “buyers beware” approach and hope that consumers will remain vigilant when buying medicinal products online.

Without legislation, regulatory authorities cannot stipulate legal responsibilities for online pharmacies or mandate that they take on quality assurance responsibilities or undergo periodic inspections. In contrast, relevant legislation empowers regulatory authorities to implement well-defined frameworks to safeguard public health (Table 2).28 –30 ,33 –44 Regulatory authorities that allow prescription-only medicines online sales can use an official accreditation system and online registries to direct consumers to legitimate sites,29 whereas regulatory authorities that prohibit prescription-only medicines online sales make it clear that no one is allowed to sell them via e-commerce.33 Additional restrictions may be imposed. For example, although China allows online sale of over-the-counter medicines, it prohibits their sales on third-party e-commerce platforms, including its very own Tmall.com.44

Jurisdictional Limitations and the Transnational Nature of Online Pharmacies

When individuals involved in illegitimate online pharmacies are based outside of a regulatory authoritie's jurisdiction, prosecution can be a challenge.45 ,46 Although most countries criminalize such acts on the basis of counterfeiting and deception with intent to harm, existing legal frameworks are fundamentally bound by territorial boundaries47

To extend jurisdiction beyond their borders or request extradition to prosecute a suspect, regulatory authorities need a harmonized set of international agreements, such as treaties or conventions48 . Even then, transnational jurisdictional claims are often met with controversies, and extradition may be difficult. Culprits may escape to countries with weak enforcement systems to avoid prosecution.

| Country | Legislation Allows Online Sale of Medicines? |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

| US | Yes: POMs and OTC medicines | State-licensed online pharmacies can sell medicinal products online.30 |

| Canada | Yes: POMs and OTC medicines | Licensed brick-and-mortar pharmacies can sell medicinal products online.28 |

| Germany | Yes: POMs and OTC medicines | Licensed brick-and-mortar pharmacies must register with the relevant RA, obtain a mail order permit, and display the EU common logo to sell medicinal products online34 |

| Great Britain | Yes: POMs and OTC medicines | Online pharmacies must register with GPhC and have a physical location in Great Britain to sell POMs.29 |

| The Netherlands | Yes: POMs and OTC medicines | Online pharmacies must register with the relevant RA and display the common EU logo issued by the RA to sell medicinal products online.35 |

| Australia | Yes: POMs and OTC medicines | Brick-and-mortar pharmacies operating in Australia can sell medicinal products online as long as they adhere to all applicable laws and practice standards36 |

| China | Yes: OTC medicines only | A bill to allow the sale of POM via online pharmacies has been delayed due to safety considerations.37 The sale of OTC medicinal products on third-party e-commerce platforms is prohibited due to safety considerations.44 |

| Japan | Yes: specific OTC medicines only |

The online sale of specific OTC medicines such as fexofenadine and loratadine is prohibited38 Other OTC medicinal products can be sold online. |

| South Korea | No: online sale of POMs and OTC medicines is prohibited |

Medicinal products can only be sold at physical stores registered with the RA.33 |

| Russia | Yes: OTC medicines only | Online sale of any medicinal products was prohibited in Russia.39 However, since December 2017, a draft law allows online sale of OTC medicinal products40 |

| India | Law is unclear | Although the RA bans the online sale of medicinal products, the prohibition is not legislated41 |

| Singapore | Yes: specific OTC medicines only |

The RA employs a “buyers beware” approach to warn consumers of the risk involved in purchasing medicinal products online.42 |

| Malaysia | Yes: OTC medicines only | The RA employs a “buyers beware” approach to warn consumers of the risk involved in purchasing medicinal products online.43 |

| Indonesia | Law is unclear | Legal status of online pharmacies is unclear.30 |

Limited Enforcement Resources

Customs agencies generally lack sufficient resources to inspect all incoming parcels. As a result, packages containing counterfeit medicines from illegitimate sources based in other countries can reach consumers, exposing them to potential harm. It is also challenging for law enforcement agencies to track down individuals involved in illegitimate online pharmacies on their own. Hence, regulatory authorities need to reevaluate their current strategies and develop international collaborative initiatives to increase the efficiency of resources spent.

Inadequacy of Cooperation by Private Organizations

Under existing laws, regulatory authorities often must rely on private companies such as delivery couriers, financial service providers, and internet companies to help en-force e-commerce regulations, and the agencies have limited options if those companies do not cooperate. For example, in 2012, delivery courier FedEx withdrew from the collaborative enforcement efforts to protest the US DEA’s decision to investigate its role in facilitating activities of illegitimate online pharmacies. In 2016, the federal charges against FedEx were dropped, and FedEx publicly criticized the US government’s decision to file charges against the company.49 Regulatory authorities must have effective legislation to mandate the involvement of private companies in eradicating illegal e-commerce, with due consideration for hold-harmless provisions.

A Strategic and Holistic Approach to Regulate Medicinal Product E-Commerce

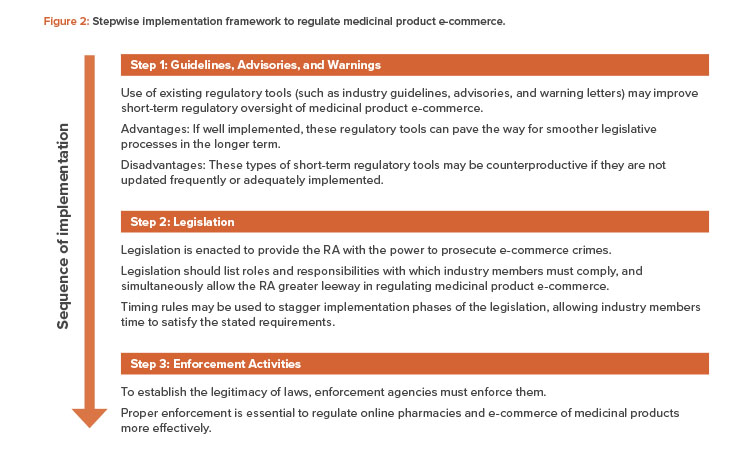

A strategic and holistic approach may help regulatory authorities more effectively regulate online pharmacies and e-commerce of medicinal products. This proposed strategic approach involves a stepwise implementation of a framework that comprises (a) guidelines, advisories, and warnings; (b) legislation; and (c) enforcement activities (Figure 2). Stepwise implementation grants companies buffer time to modify their in-house policies to align with directions set by the regulatory authorities with oversight power. The success of the approach lies in the collaboration of the authorities (domestic and international) with various organizations (accreditation organizations, Interpol, and private companies).

In countries that currently lack laws to effectively govern e-commerce of medicinal products, the domestic regulatory authorities should initiate a national licensure system for all online pharmacies operating under their jurisdiction to allow for regulatory oversight. A mandatory inspection or accreditation framework may be included in the licensing requirement to ensure that the online pharmacies meet internationally recognized quality system standards.

- 27

- 28 a b c

- 32World Health Organization. “Safety and Security on the Internet: Challenges and Advances in Member States: Based on the Findings of the Second Global Survey on eHealth.” Published 2011. https://www.who.int/goe/publications/goe_security_web.pdf

- 30 a b c

- 33 a b c Korea Law Translation Center. “Statutes of the Republic of Korea, Pharmaceutical Affairs Act.” Accessed 11 June 2019. https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_service/lawView.do?hseq=40196&lang=ENG

- 44 a b c Jing, M. “China FDA Stops Online Med Sales.” China Daily USA. Updated 2 August 2016. http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/epaper/2016-08/02/content_26317670.htm

- 29 a b

- 45Terry, N. P. “Regulatory Disruption and Arbitrage in Health-Care Data Protection.” Yale Journal of Health Policy, Law, and Ethics 17, no. 1 (2017): 143–208. https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yjhple/vol17/iss1/3

- 46United Nations Treaty Collection. “Status of Treaties: United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime 2003.” Published 15 November 2003. https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XVIII-12&chapter=18&clang=_en#EndDec

- 47Baker, E. “The Legal Regulation of Transnational Organised Crime.” In Transnational Organised Crime: Perspectives on Global Security, 183–193. Oxford, UK: Taylor & Francis Group, 2003.

- 48Ryngaert, C. “Universal Jurisdiction in an ICC Era: A Role to Play for EU Member States with the Support of the European Union.” European Journal of Crime, Criminal Law and Criminal Justice 14, no. 1 (2006): 46–80. doi:10.1163/157181706776986191

- 34German Institute of Medical Documentation and Information. “Online Medicine Retailers.” Accessed 11 June 2019. https://www.dimdi.de/dynamic/en/drugs/online-medicine-retailers

- 35Ministerie van Volksegezondheid, Welzijn en Sport. “Online Providers of Medicines.” Accessed 11 June 2019. https://www.aanbiedersmedicijnen.nl

- 36Pharmacy Board of Australia. “Guidelines for Dispensing of Medicines.” Accessed 11 June 2019. http://www.pharmacyboard.gov.au/documents/defaultaspx?record=WD10%2F2951&dbid=AP&chksum= WMyYdhKfX3%2BWGPiGUCLsMw%3D%3D

- 37Yuan, P., L. Qi, and L. Wang. “Controversy in Purchasing Prescription Drugs Online in China.” Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 37, no. 8 (2016): 623–4. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2016.05.007

- 38Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. “List of Sales Sites for over-the-counter Drugs.” Accessed 11 June 2019. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/iyakuhin/ippanyou/hanbailist

- 39Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. “Global Forum on Competition: Contribution from the Russian Federation on Competition Issues in the Distribution of Pharmaceuticals.” Published 30 January 2014. http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=DAF/COMP/GF/WD(2014)33&docLanguage=En

- 40Goryachev, I. “Russia Federation: Telemedicine Law in Russia,” Mondaq. Published 22 February 2018. http://www.mondaq.com/russianfederation/x/675838/Healthcare/Telemedicine+Law+In+Russia

- 41Ganapathy, N. “India’s Pharmacies Do Battle with Online Rivals.” The Straits Times. Published 12 June 2017. https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/south-asia/indias-pharmacies-do-battle-with-online-rivals

- 42Health Sciences Authority of Singapore. “Dangers of Buying Health Products Online.” Updated 6 June 2018. http://www.hsa.gov.sg/content/hsa/en/Health_Products_Regulation/Consumer_Information/Consumer_Guides/Dangers_of_Buying_Health_Products_Online.html

- 43Ministry of Health of Malaysia. “Buying Medicines Online: Beware.” https://www.pharmacy.gov.my/v2/en/website/waspada-belian-ubat-online

- 49Tribune News Services. “Prosecutors Drop Illegal Prescription Drug Trafficking Case Against FedEx.” Published 17 June 2016. http://www.chicagotribune.com/business/ct-fedex-drug-trafficking-case-dropped-20160617-story.html

Pharmaceutical companies may assist regulatory authorities to expedite the inspection process by reconciliation with their respective supply chain partners to confirm that medicinal products sold by the individual online pharmacies originate from a legitimate source. Upon satisfactory inspection, online pharmacies will be given country-specific accreditation seals for their websites and added to the online pharmacy registry found on the regulatory authoritie's website.

Ultimately, the online pharmacies licensed by the regulatory authorities should be hosted on the “.pharmacy” domain operated by NABP, regardless of the countries in which they operate. This initiative will mold the “.pharmacy” domain into the standardized domain and international benchmark for legitimate online pharmacies worldwide, helping consumers verify a pharmacy’s legitimacy from its web address. To address challenges beyond the scope of NABP and ensure neutrality of the accreditation system, ownership of the “.pharmacy” domain may be transferred to a neutral international nongovernmental organization such as the World Health Organization or an appropriate United Nations agency.

In addition to creating a safe e-commerce environment for medicinal products, it is vital for regulatory authorities to educate consumers on how to access and use the secure e-commerce environment for medicinal products. Regulatory authorities may consider collaborating with search engine providers such as Google to use online advertisements to spread educational messages; another option might be to employ behavioral advertising techniques, like retargeting, to direct educational messages selectively to consumers at risk of engaging in unsafe e-commerce practices.50

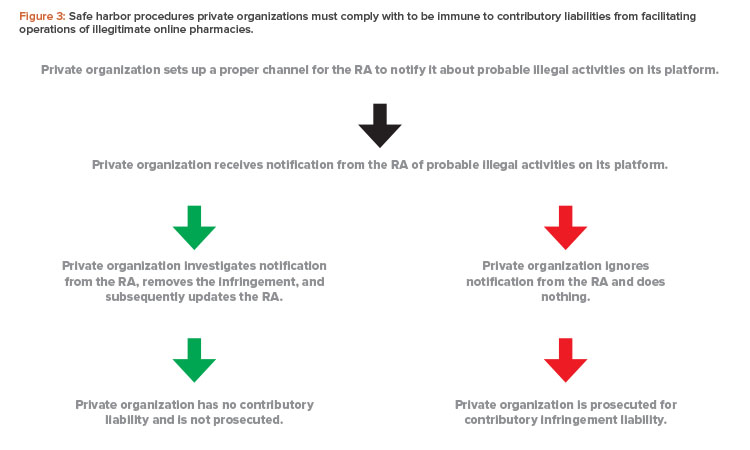

Moving forward, regulatory authorities should consider working in partnership with private companies such as delivery couriers, search engine providers, domain name registrars, financial service providers, and online platform owners in the overall regulation of online pharmacies (Table 3 and Figure 3). These private organizations should have self-regulation guidelines or policies to curb the proliferation of illegitimate online pharmacies. The self-regulation guidelines, which should be agreeable to the regulatory authorities, should contain reasonable precautions that private organizations could adopt to prevent individuals from exploiting their services, regardless of whether they are online or offline.51

Subsequently, regulatory authorities should consider enacting legislation with adequate regulatory bite to mandate that private organizations implement reasonable precautions. Regulatory authorities can also incorporate safe harbor procedures (Figure 3) into the new or amended legislation to incentivize private organizations to collaborate to stop illegal acts, to proactively investigate any illicit activity at their end, and to avoid any legal contravention.52 The regulator and regulated should share a common understanding, with due consideration for hold-harmless provisions, to avoid any liability issues.

| Type of Organization | Reasonable Precautions |

|---|---|

| Delivery courier |

|

| Search engine provider |

|

| Domain name registrar |

|

| Financial service provider |

|

| Online platform owner |

|

- 50Anderson, A. C., T. K. Mackey, A. Attaran, and B. A. Liang. “Mapping of Health Communication and Education Strategies Addressing the Public Health Dangers of Illicit Online Pharmacies.” Journal of Health Communication 21, no. 4 (2016): 397–407. doi:10.1080/10810730.2015.1095816

- 51Bernstein, D. H., and M. R. Potenza. “Why the Reasonable Anticipation Standard Is the Reasonable Way to Assess Contributory Trademark Liability in the Online Marketplace.” Stanford Technology Law Review 9 (2011): 1–21. http://stlr.stanford.edu/pdf/bernstein-reasonable-anticipation.pdf

- 52Sunderji, F. S. “Protecting Online Auction Sites from the Contributory Trademark Liability Storm: A Legislative Solution to the Tiffany Inc. v. eBay Inc. Problem.” Fordham Law Review 74 (2005): 909–46. http://fordhamlawreview.org/issues/protecting-online-auction-sites-from-the-contributory-trademark-liability-storm-a-legislative-solution-to-the-tiffany-inc-v-ebay-inc-problem

Concurrently, it is crucial for regulatory authorities to work together and with Interpol to step up international enforcement efforts against illegal sales of medicinal products online.53 This will allow prosecution of suspects involved in illegal online sales of medicinal products, regardless of where the crime was committed. Penalties should be raised proportionately to provide deterrence.

It is crucial for regulatory authorities to work together to step up international enforcement efforts against illegal sales of medicinal products online.

Interpol needs to take on the central policing role of illegitimate online pharmacies and establish an independent international task force to conduct investigations at the global level. This task force would facilitate essential intelligence exchanges among regulatory authorities and lead a collaborative investigation with national law enforcement agencies to track down suspects.54 Such international collaboration can vastly improve the efficiency of investigations and help authorities conserve resources.

Conclusion

E-commerce of medicinal products is expected to become an integral part of healthcare systems in the future. Increased e-commerce of medicinal products can bring about advantages such as lower cost, convenience, and consumer privacy. However, the shift from physical stores to online platforms also presents health risks.

Many regulatory authorities lack legislation to properly regulate online pharmacies. Jurisdictional and resource limitations have allowed criminals to escape prosecution. The lack of legislation to mandate private organizations’ cooperation in investigations also impacts enforcement efforts negatively.

Going forward, a proposed strategic and holistic approach may help regulatory authorities regulate e-commerce of medicinal products more effectively. This strategic approach—which incorporates a stepwise implementation of industry guidelines, advisories, and warnings; legislation; and associated enforcement activities—can address the current risks associated with illegitimate online pharmacies and illegal medicinal product e-commerce. Although compliance costs may increase with tighter e-commerce regulation of medicinal products, safeguarding public health should ultimately be the overriding concern of all RAs and stakeholders in general.

- 53Attaran, A., D. Barry, S. Basheer, R. Bate, D. Benton, J. Chauvin, et al. “How to Achieve International Action on Falsified and Substandard Medicines.” British Medical Journal 345 (November 2012): 1–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.e7381

- 54Brocklesby, J. “Using Systems Modelling to Examine Law Enforcement Collaboration in the Response to Serious Crime,” 13–34. In Applications of Systems Thinking and Soft Operations Research in Managing Complexity. New York: Springer, 2016.